Region of contrasts

After reform and merger in 2016, the central France region of Limousin was subsumed into the new, much larger region Nouvelle-Aquitaine, yet still manages to retain its timeless character and charm.

The former region of Limousin was, at the start of the new millennium, touted as a major destination for Britons seeking a holiday or permanent home in France, boasting unspoilt countryside and a plethora of affordable properties. As a former resident, I revisited an article I wrote for Destination France magazine way back in 2008, to gauge how, and if, it had changed in the intervening years.

France is divided into eighteen administrative régions, thirteen in metropolitan France, with the remainder being oversees. A law passed by parliament in 2014 reduced the number of metropolitan regions from twenty-two to thirteen, effective from 1st January 2016. After reformation and merger of the regions, new names were confirmed by the Conseil d’état by 30th September 2016. Limousin, along with Aquitaine and Poitou-Charentes, became Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the largest administrative region by area, a whopping 84,035.7 km2. It has a population of more than 6,033,952, stretches to the western coastline, and includes a substantial chunk of Southern France. Whereas Limousin contained three départements – Haute-Vienne, Creuse, and Corrèze – the newly defined region has twelve, adding Charente, Charente-Maritime, Dordogne, Gironde, Landes, Lot-et-Garonne, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Deux-Sèvres, and Vienne. By contrast, Limousin had covered an area of 17,000 km2 with a population of less than 800,000 inhabitants, making it the least populated region of metropolitan France. This abridged article focuses on the départements of Limousin before reform and merger.

An area of low-lying pastures and tablelands, it is grazed by tan-coloured cattle and flocks of sheep. Graced with thousands of étangs, ponds, natural and man-made lakes, it caters for fishing, swimming, canoeing, sailing, windsurfing and other watersports. Criss-crossed by leafy paths, it’s a haven for ramblers and nature lovers, for cyclists there are traffic-free roads, while for mountain-bikers rugged, off-road trails. Intersected by rivers bristling with fish, it’s a lure for anglers.

The three départements – Creuse in the north-east, Haute-Vienne in the north-west, and Corrèze in the south – are situated on the north-western edge of the Massif Central mountains, bordering the Centre region in the north (now Centre-Val de Loire), Auvergne in the east (now Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes), Poitou-Charentes and Aquitaine in the west, and the Midi-Pyrénées in the south (now Occitanie). The region is served by daily flights from London Stansted and Manchester airports, and seasonally from East Midlands, Leeds/Bradford, and Bristol airports direct to Limoges-Bellegarde. Brive-Souilliac airport in Corrèze, which opened in 2010, offers direct connections to London Stansted. (After the merger, Poitiers airport in Vienne to the west also offered direct flights to the UK, as did Bordeaux in Gironde, Bergerac in Dordogne, and Pau in Pyrénées-Atlantiques.)

By car, Limousin is six to eight hours’ drive from Calais, on fast autoroutes.

Understated allure

The region is of geographical, architectural, climatic, and cultural contrasts, linked by unprepossessing charm. The populace is thinly distributed through villages and hamlets. Inhabitants are friendly, obliging, quietly curious, by and large welcoming the hordes of foreigners drawn there. They regard the influx as a breath of life, for the area has an ageing, dwindling population. Largely composed of agricultural land, it may not exude the picture-postcard beauty of France’s traditional tourist haunts, but has understated allure. Although the majority of properties are utilitarian farmsteads or workers’ dwellings, many towns and villages boast splendid medieval architecture. City-dwelling inheritors of properties are reluctant to move to the countryside, where work is scarce and entertainment modest; hence houses are frequently abandoned.

While many hamlets retain an unsophisticated rural atmosphere, the foreign contingent often outweighs the French, threatening to dilute their character. Customarily drawn to elderly, remote properties, many foreign buyers now opt for village or town houses. Having suffered closure of independent shops, villages are witnessing a slow return of life to deserted streets. Families relocating to the region seek schools, thriving commerce, perhaps a business opportunity: there are numerous British-run bars, restaurants, shops, bed and breakfast establishments and gîtes in the region. Supermarkets and do-it-yourself stores thrive on the outskirts, many doubling their size, partly due to increased trade from foreigners. Stores pander to their English clientele, with aisles of imported foodstuffs. When tempted by a remote property, bear in mind that the nearest shop may be a car ride away, even for basic daily needs. The tradition of travelling vans servicing remote villages with bread, meat, frozen food and other provisions, has all but died out.

A slower pace

Britons contemplating relocating to these départements should not be lulled by the long, hot summers they enjoy, for the winter climate can produce copious rainfall, bitingly cold temperatures and heavy snowfalls. Winter sports fans won’t be deterred, however, since the ski slopes of neighbouring Auvergne are only three hours’ drive away. Spring and summer is time to savour outdoor life, and fêtes blossom throughout the region, on lakeshores or in village squares. Despite this, the region remains low key and olde-worlde – in itself relaxing – although out of season there’s little entertainment. Restaurants serve well-cooked, inexpensive dishes, but in my opinion, typically brightly lit interiors lack finesse. Where effort has been made to infuse character, this often appears old-fashioned or kitsch. Bar-tabacs are generally male haunts with Formica tables and plastic chairs. Habitual early closure – often before nine o’clock – means nightlife can be staid for Brits used to the conviviality of village pub culture.

Haute-Vienne

Until UK television programmes, magazine features, and property agents began promoting the region, Haute-Vienne had not been regarded as the destination for masses of holidaymakers because, mainly given over to agriculture, it has little infrastructure to support tourism. The terrain is flattish, open countryside, receiving the brunt of winds tearing across from the Atlantic, bringing much rainfall. The soil is infertile for major crops, although sunflowers and maize thrive, and pastures, peppered with stands of oaks, are grazed by cattle and sheep.

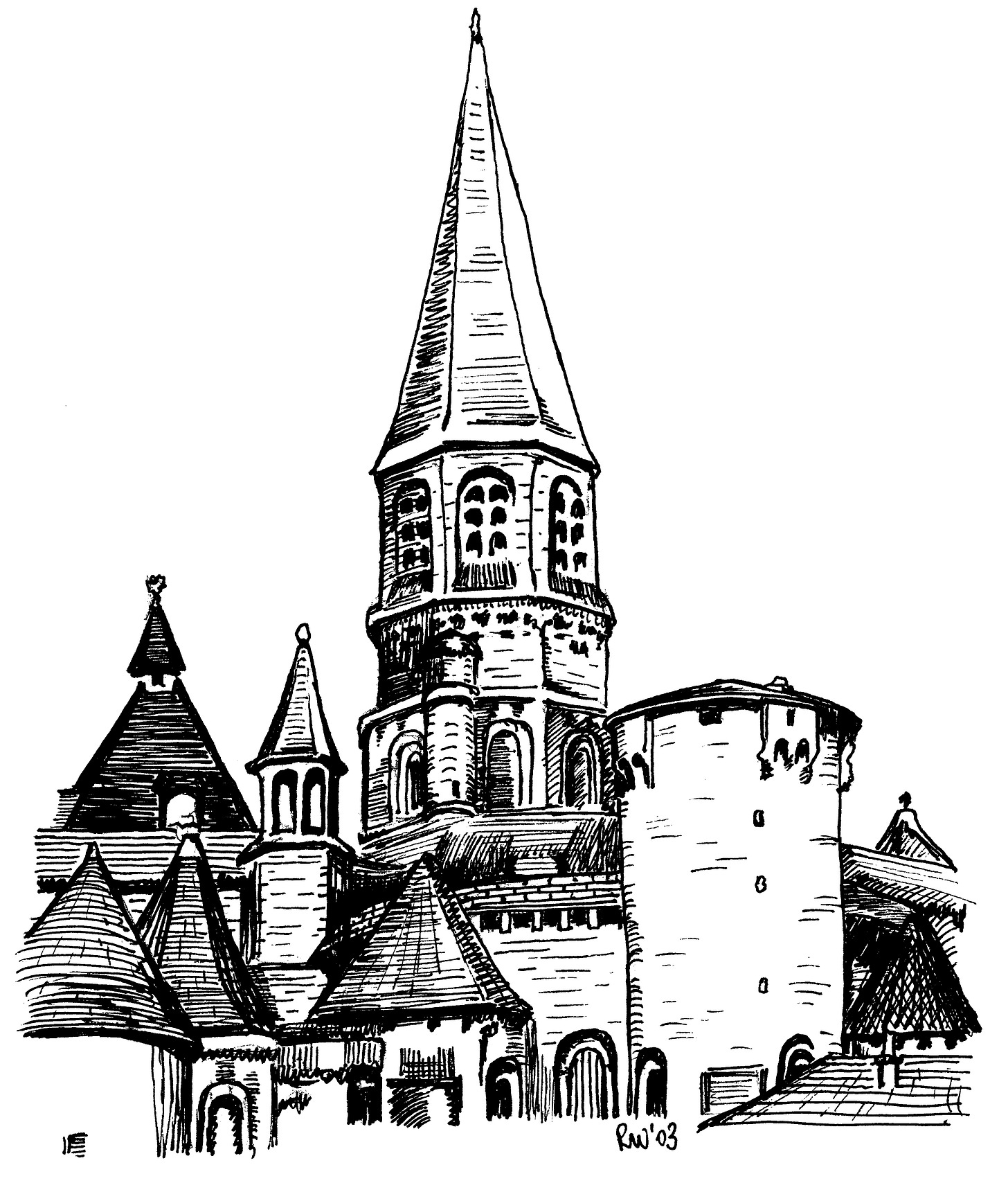

Le Dorat is a charming ville of narrow streets of medieval buildings, dominated by the gothic, octagonal belfry of the fortified Collegiate de Sainte-Pierre, with its soaring stone spire. An equestrian arena in the town centre is a venue for show jumping events, while on the outskirts the Hippodrome hosts horse racing, June to August. In addition to flat racing and steeplechasing, there is also harness racing, with horses driven by a driver perched on a lightweight two-wheeled buggy of American origin, the sulky. The town also holds crafts days, concerts and a Christmas market; there’s a cinema, offering films in English.

Nearby Bellac is a historic market town overlooking the pretty Vincou river valley, with pleasant shops, bars and lively restaurants, and an open-air market selling local produce and wines. The town is close to Lac Saint Pardoux, a favourite venue for watersports.

Mortemart, the only Haute-Vienne village to be classified as one of the most beautiful in France, was built around a 10th century château, of which the keep and guard’s room remain, and was the site of a 1330 Carmelite monastery. This sumptuous village has, at its centre, a 17th century, open-sided, roofed marketplace, selling farm produce on Sundays during July and August. Beyond Mortemart, the terrain rises to the slopes of the Monts de Blond, scattered with megaliths: dolmen (burial chambers) and menhirs (standing stones) – see next week’s Waymarks for more on these!

To the southeast, Limoges (formerly Limousin’s capital, but now the prefecture of Haute-Vienne), is renowned for its fine, white porcelain. The city sits on low hills overlooking the Vienne river, and enjoys a microclimate. The gothic bell tower and flamboyant portal of Saint-Etienne cathedral, overlooking the botanical Jardins de l’Eveche, whose terraces step down towards the river, dominate its skyline. Vying for attention is the mosque-like, sixty-metre art deco campanile and green copper dome of Benedictins railway station, providing trains to Paris in three hours. The city’s riverbanks are accessible by tree-lined paths, the river crossed by the graceful arches of 18th century Saint-Martial Bridge, built on roman foundations. The Château district features medieval, half-timbered buildings with restaurants, bars and cafés opening onto sunny squares. The Quartier des Bouchers, domain of meat traders (descendants of the original six families to set up business there) contains the tiny Chapelle Saint Aurélien, built by the Guild of Butchers to house relics of their patron saint.

For lively entertainment, this university city boasts nightclubs, a wealth of cosmopolitan restaurants, cinemas and theatres. For those who would prefer to live within the bustling city, there are developments of one-, two-, or three-bedroom apartments, and five minutes from the centre, compact studios.

To the southeast of Limoges, on the banks of the Vienne, architecture becomes more refined, such as the medieval style of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat, on an ancient pilgrim trail, and the fortress town of Eymoutiers.

Creuse

The Creuse is one of the least populated départements in France, an oasis of hilly pastures, oak and chestnut forests. The Grande Creuse river, intersecting the countryside, was dammed to create three lakes in the valley from La Celle Dunoise through Le Bourge d’Hem, and Champsanglard to Glénec. Well stocked with fish, they also offer quiet, sandy beaches, swimming and watersports. Nearby can also be found sprawling Lac de Vassivière, grandest of the Creusois lakes.

Apart from a history of skilled masons, the Creuse is noted for its tapestries and weaving, for which Aubusson is renowned. Its Musée départemental de la Tapisserie houses exhibitions tracing the history of the skill from the 15th century to the present day. This charming town straddles the Creuse river, its medieval houses adorned with turrets, carved stone windows and doorways.

La Souterraine is an affluent market town with many medieval buildings, and surviving ramparts of a fortified town, including the Porte de Saint-Jean. The town’s railway station is served by TGV trains from Paris in three hours, and links to the south of France. In the northeast, Boussac lies between hilly Auvergne, the plains of Berry, and forested areas to the south. Encircled by Le Petite Creuse and Le Beroux rivers, the town is tranquil, with mellow, brown-roofed buildings, stone spiral staircases and wrought-iron balconies. There’s also a gothic château, housing intricate tapestries, where author George Sand set her novel Jeanne. The surrounding countryside features beguiling gorges beloved of impressionist painters from the Ecole de Crozant, including Monet and Renoir.

Guéret, capital of the Creuse, lies close to Lac de Courtille, while south of the town are the Monts de Guéret and the Forêt de Chabrières, containing Les Loups de Chabrières, a park where visitors can observe packs of wolves.

Corrèze

The geography of Corrèze is dramatically different, a rugged, hilly area through which the Vézère, Dordogne and Corrèze rivers flow, feeding lakes, gorges and waterfalls. The landscape is clothed with beech and chestnut trees. The Plateau de Millevaches is a vast, undulating upland on the northern edge of the Massif Central, with stunning panoramas. Sparsely populated, its few habitations austere buildings of local stone.

The architecture of Corrèze is more elegant, with sand-coloured stone walls, and distinctive rooflines. Here are six of France’s plus beaux villages. One is the 11th century bastide, fortified village of Turenne, whose château dominates a rocky pinnacle, with slate-roofed houses clustered around, linked by steep, winding, cobbled lanes. Properties in this sought-after village are rare and consequently fetch high prices.

Another beautiful Corrèzien village is Collonges-la-Rouges, its ancient houses boasting fairytale towers and vaulted porches. Built from red sandstone, many of the buildings are designated as historical monuments. The intense red coloration of the soil in the area is due to high levels of iron oxide present during the solidification of the sand grains 250 million years ago.

Ségur-le-Château, quaintest of the six gems, occupies a delightful setting in a curve of the Auvézère river, with castle ruins above a jumble of half-timbered buildings. Waymarked trails lead from the village through ravishing countryside. The village is one of a line of château towns whose defences were strengthened against Richard the Lionheart’s crusade, and include picturesque Chálus (where he died), Nexon, Rochechouart, Arnac-Pompadour (home of a National horse stud and location of a popular racecourse), and Montbrun.

Capital of the département is Tulle, a town of narrow, medieval houses and steep streets, built on hills intersected by the Corrèze river. Renowned for the accordions that typify French folk music, Tulle is home to a museum, the Cité de l’accordéon et des patrimoine, and hosts an annual festival celebrating the instrument. Although not large, Tulle has a cinema, theatre, sports centre, aqua-recreational centre, general hospital and maternity home, excellent primary schools, a sixth form college, and higher education facilities.

Brive-la-Gaillarde, one of the liveliest towns in the three départements of former Limousin, has weekly markets, an onion fair, and music festivals during summer, truffle markets in winter, and a book fair in autumn.

Limousine cuisine

Limousin has a tradition of gastronomy based on high quality, locally produced ingredients. While the brown Limousin cattle produce beef of outstanding taste and texture, and the succulent Cul-Noir, ‘black bum’ pig from Saint Yrieix-la-Perche, marries well with the region’s golden apples, the feast does not end there. Traditional dishes include Clafoutis aux cerises, a sweet batter cherry tart; and the massepain (marzipan) of Saint Léonard-de-Noblat in the Creuse. Saint-Yrieix is also famous for its petit fours, madeleines, and delicate veaux, veal. Brive-la-Gaillarde is proud of its mustard, moutarde violette, while the southern walnut groves yield a potent liqueur de noix. Cheeses include brebis, made from ewe’s milk, and gouzon of the Creuse, a curd for only the brave (as referred to in a previous Waymarks, Trial by Cheese).

Lakeland Limousin

Many of Limousin’s lakes have safe swimming areas ideal for children, often with playground facilities, or a pétanque pitch. The water laps onto man-made, sandy beaches, and most lakes are monitored by lifeguards. Grassy areas are ideal for picnicking, while lakes are located amidst glorious countryside. Well-marked paths circuit some lakes. The larger lakes have cafés or restaurants offering ice-cream, drinks, snacks, or local cuisine – popularly moules et frites – and many are venues for firework displays and summer fêtes. Notable lakes include:

• Lac de Vassivière Constructed in the 1950s, this Creusois lake is one of the largest in Europe, covering more than 1,000 hectares. Facilities include a nature reserve, an island with contemporary arts centre, boat trips, cute villages nestled around its circumference, 300km of trails, and sandy beaches.

• Lac de Saint Pardoux This Haute-Vienne lake covers 330 hectares, has several swimming areas, beaches and shady areas, cafés, horse and pony trekking, kayaking and canoeing on the lake or adjoining rivers, plus sylvan walks. At one beach area is a flume, popular with children.

• L’Etang de la Chaume Located close to Azerables, in Creuse, this lake lies on sand and, fed by streams, is extremely clean. There’s a modest beach, a children’s play area, a pétanque pitch, and a birdwatching centre. Sailing proficiency courses are offered, as is pedalo hire.

• Lac de Mondon In Haute-Vienne, this small lake has a swimming area, café and adjoining campsite. A wooded circuit leads from the lake along the banks of the river Benaize, past white water rapids and the bubbling waters of the Pot Bouillant, and back to the lake.

Defiant stance

Despite becoming part of the sprawling Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the three départements are still collectively known as Limousin, referred to as such on numerous tourist and town websites, as a ‘historical region’. It has, therefore, managed to retain its unique identity in the face of sweeping change.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this essay, you may like to read my humorous travel books Bon Courage! and Bonne Chance! both which are set in Limousin. You an obtain them via my website. Thank you for reading!

Thanks Kate! I'm pleased you found it interesting.

Such a fully complete and comprehensive summary. So interesting & informative at the same time. I love this post.